ECONOMICS

Emissions trading is an administrative, market-based approach for achieving reductions in the emissions of pollutants, by providing economic incentives to polluters to encourage compliance in cap-and-trade regimes.

While emissions trading began in the United States in the 1990s with a regional sulfur dioxide cap-and-trade program, global greenhouse gas markets are a relatively recent phenomena.

It was only since the move toward the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol began that the rush to commodify airborne pollutants has gained momentum.

The logic of emissions trading is that polluters require an economic incentive to switch to less polluting practices. By commodifying pollution reduction, polluters will be more inclined to meet their pollution reduction obligations.

This strategy exists in contrast to other approaches that would force polluting industries to reduce or stop their polluting activities outright.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

THE KYOTO PROTOCOL

The Kyoto Protocol is a 1997 agreement for countries to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases, or engage in emissions trading if they increase their emissions.

The Kyoto Protocol contains a ‘cap-and-trade’ mechanism component, through which polluters that control their emissions by reducing them to levels under the ‘cap’, may monetize the ‘unemitted’ difference as carbon credits. These credits can be sold to other pollutors in Annex I nations that don’t meet their targets during the first period of Kyoto, from 2008-2012, or sold speculatively by traders.

The system is haphazard, as for example, there could be a creation of credits resulting from the collapse of a country’s economy. However, conversely, in this model, a country might have to pay for the environmental costs of waging war.

While the Kyoto Protocol didn’t come fully into force until 2005, there were already prototype emissions markets operating for buying and selling pre- and extra-Kyoto compliance and noncompliance offsets.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

WHO BENEFITS?

Perhaps private investors via the World Bank Prototype Carbon Fund, which along with the Dutch Government’s ERUPT/CERUPT ‘carbon tenders’ accounted for over half of the volume of deals closed in 2002. (Souce: PWC).

In 2006, a £1bn windfall for carbon trade firms was projected to result from the EU Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme “because many firms have benefited from increases in electricity prices brought about by the scheme without needing to make any extra investment in return”. Peter Bedson, from IPA Consulting, said that part of the problem was that firms had been given, free-of-charge, the carbon emissions permits on which the scheme is based. This, he explained, was like the government giving energy firms free money.” (Source: BBC)

Ultimately, as the logic of privatization points to the commodification of all common pool resources, a reduction model based on trade is contradictory to a socially just solution to global air pollution. We need another model.

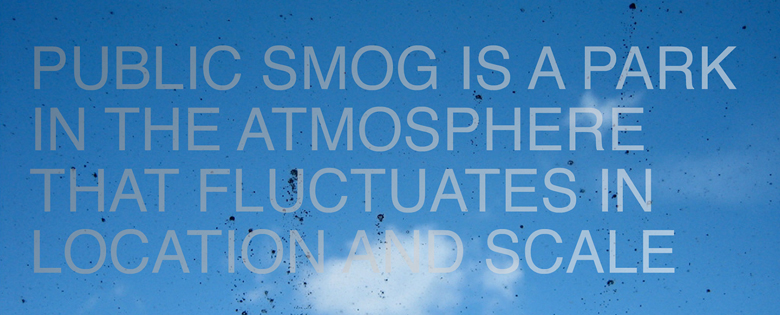

In the meantime we have PUBLIC SMOG, a way for the global public to buy back the sky on the open market.